Reprinted from James Taylor's Book:

"CAIRNTABLE ECHOES."

A History of Muirkirk Ironworks

1787-1863

—————————

An Extract from the Minutes of

Muirkirk Literary Association and Lapraik Burns Club

—————————

JANUARY 18, 1927:—

The following is the text of a lecture given under the auspices of the Burns Literary Association, in the Dundas Hall, on 18th inst., by Dugald Baird, Esq., Kameshill.

HISTORY OF MUIRKIRK IRON COMPANY

1787-1863

In the late Col. J. G. A. Baird's little book, "Muirkirk in By-gone Days," p. 44, he says "It would be an interesting task to trace the progress of these industries from their beginning in the Parish to the present day, but unfortunately the information needed is wanting.

Then on p.45 he continues—"Some day it may be that further light will be thrown on this interesting phase of our staple industry. Some day other gaps in its history may be filled up, otherwise the story of the Parish can never be complete."

While perusing some old letters and reports left behind them by the Muirkirk Iron Company, it occurred to me that at least a gap of 76 years could be filled up, if a short history of the old Muirkirk Iron Company was given; as taken from the letters and reports referred to, which would leave a further gap of 64 years to bring it up to date. This further gap is not being dealt with at the present time, but whoever takes it up will have plenty of data to go by; and besides quite a number of the older members of the community have been in Muirkirk during the greater part of this period, and so have plenty of material to go on with at first hand.

With the exception of Haematite ore mining on Whitehaugh and iron forging at Torreoch (1705-1732), there appears to be no record of coal or iron mining before 1787, the advent of the Muirkirk Iron Company, but it is likely that at least coal was mined both North and South of the Water of Ayr before that date. We, however, begin from 1787, and to enable us to visualise the date more readily, it might be mentioned that at that time, George III. was on the throne—the Poet Burns was 28 years old and no doubt passed through our village on his way to and from Edinburgh, and, as Lapraik was at that time living at Dalfram, most likely Burns would look in to see him. According to the dates on her tombstone in the Parish Churchyard, Tibbie Pagan would be 46 years old then, and did nit die for 34 years thereafter, being 80 years old when she died.

EXTRACTS FROM REPORT BOOKS KEPT BY THE MANAGERS

AT MUIRKIRK, BEGINNING MARCH, 1787

On that date Messrs Robertson, Gillies, and Edington (in those days the Old Company was composed of Glasgow business men)—Mr Baird said—journeyed from Glasgow to Muirkirk via Sorn. At Sorn they found some ironstone and coal, but neither of them good quality.

Two miles east of Sorn they examined the bed of a burn which flows into the Ayr, and took samples ironstone for analysis. They also visited the Whitehaugh and saw the iron-ore veins which had been previously worked by Lord Cathcart, but in 1787 were belonging to Mr McAdam of Craigengullen.

Afterwards they came to Muirkirk and measured the properties adjoining Kames Estate (then on lease to Captain Cochrane)—Ashyburn, Crossflat, Auldhouseburn, Bankend, and Camshill (Kameshill). They also examined on Tordoes (spelt Tardoors) and found Ironstone in the burn east of the house. On Tordoes they found veins of iron ore. Mr Gillies leveled the Water of Ayr from Crossflat-Waukmill to Kameshill, and found 752/3 feet of Fall, but the figures were thought to be too much, as the day he leveled it was one of continuous wind and rain, and there might have been a mistake made. It was proposed to erect a dam at the low end 30 feet high, so as to get the water power to blow one blast furnace. This plan, however, was not carried out. Mr Grieve, the resident manager, was to look into the whole question at Muirkirk. He was also to visit Kilmarnock and Clelland to see if the coal and ironstone there was good, as "nothing can induce us to go into such a desert place as Muirkirk, but the absolute certainty of having the coal, ironstone, and limestone very cheap.

If Mr Grieve can therefore find the materials nearby as moderately at Kilmarnock or Clelland, we cannot for a moment hesitate to abandon Muirkirk.

In no instance is Mr Grieve to pay a fixed rent, as we wish to give them up whenever they are not worked to profit ("Sound judge" ventured Mr Baird).

However, they agreed to continue at Muirkirk, and in August, 1787, gave Mr Grieve directions to build a Furnace and an Engine, and to do all in his power to have them built and covered in before winter to save reflections on himself and his friends.

He also got instructions to build what is now called the 'Red Row,' the roof and windows to come from Leith, and the tiles from Glasgow. But if the expense of carting tiles from Glasgow was too great, it was to be slated, if this did not cost more than 20/- per rood, slates being preferred owing to the situation being so exposed. Mr Grieve was also to set miners to work to prove the ironstone and start the great level (running South from the Water of Ayr near the Works low gate, and this still exists): also to continue the Ore Mine as formerly at the Black Hill (Tor Dhu) which is still open.

In October, 1787, Mr Gillies was to make the plates for a boiler of the very best iron, and that Mr Grieve was not to put into it any plates that were in any way cracked or unsound, lest it should at any period stop the Furnace.

Mr Strang has behaved so shabbily in the transactions about Tordoes Farm that Mr Grieves is to be cautious of having any further connections with him.

Now that we have sufficient Ironstone for one Furnace "we have a good reason to be afraid of Commodore Stewart or Lord Dundonald's schemes."

We should not purchase any land at Muirkirk, but should erect cheap buildings, and whenever the coal and iron ceases to be got cheap we should abandon them, and take our machinery elsewhere.

The object of Mr Grieve is to get the Furnace and Cast House finished as soon as possible and blow in the Furnace early in summer. Mr Gillies to engage a vessel to bring the cylinders from Chester—it to have hatches wide enough to take in a cylinder seven and a half feet wide ("I believe that same cylinder is lying down at the Holm yet" said the lecturer).

At a meeting held at Muirkirk, 11 day of March, 1788, Captain Cochrane (afterwards Lord Dundonald) offered char (coke) from the Tar Kilns at "Coombs" at 1/8 at the Kiln, or 2/- per ton at the Furnaces, and it was agreed to make a trial of it.

A contractor, or undertaker, as they were known at that time called, was to be got to deliver limestone at 1/8 per ton, broken to the size of hens' eggs.Robert Neil offered to do this.

John Paterson, the mason, was to build the Fire Engine, and the Air Vessel to the west of the Cast House.

It was resolved to continue the level of the vein of Iron-ore in the Eastern Hill of Tordoes.

The foundation of the second Furnace was not to be laid down at present, for of water is used to blow the Furnace, then No. 2 Furnace will be build below No. 1 so that the same water can be used twice. The Coke Yard to be near enough to the Furnaces so that the grade up to it be only one in 16.

As few buildings to be erected as possible—"Many manufacturers destroy themselves in building houses. Carron is an melancholy example of this."

As to Commodore Stewart (Laird of Wellwood), we have no hold over such a Jew, but his interest.

The Laird of Kames told us that Nether Wellwood was better worth £6,000 than the other was worth £4,000.

Thomas Edington, one of the partners, wrote to Mr Grieve—"Your man as I am told is a drunken dog. You will therefore be careful that he does his work properly and not get into our debt."

If Mr Strang does not get carts to carry the timber for the beam in a few days, I will write you to get the logs from Ayr. In April, 1788, it was agreed that the road to Sanquhar should be on the West side of the Works, and not through them, as was first proposed.

In September, 1788, Workings were commenced at Auldhouseburn, and George Espie and three others worked there at an opencast and produced 12 to 14 tons of coal per week at 2/- per ton—7/- per week each.

Iron-ore at Tordoes—100 tons in stock. The streak of the veins in both East and West Hills runs North and South. That, in the Western Hill dips to the West; that in the Eastern Hill dips to the East. That in the East Hill is un favourable, on the West Hill a Pit was being sunk. At one fathom down the vein was one foot wide, at five fathoms it was two feet wide. Limestone easily to be had, and in abundance.

2nd September, 1788:Mr William Caddell joins the Company as Mr Edington's representative and was to get a Receiver Cover cast at Carron, if it could be got at Clyde Iron Works, from the Pattern being made by the Joiner at Muirkirk.

The next meeting was held in Glasgow on October, 1788, and the following persons were present:—George Bogle, John Robertson, Peter Murdoch, James Gordon, James McDowall, and John Gillies. Mr Gillies reported that he had been to Muirkirk and there met Loudon MacAdam, who offered Coke at 2/3 per ton.

All the Limestone got at Crossflat to be carted home before winter sets in.

Mr Grieve wishes to let to Thomas Richmond of Linburn that portion of Tordoes Farm, north of Greenock Water for £5 per year (There was now no land belonging to Tordoes north of Greenock Water, so far as Mr Dugald Baird knew).

Mr Grieve was also to set about and make a plan of a house for himself, and send it to Glasgow for approval.The stones to be got locally. He is also to let it to a mason. A. carpenter from Ayr or Glasgow to contract for doors, windows, and flooring, and get it ready for occupation early in Spring.

15th November, 1788, at Muirkirk:—Mr Grieve to see Commodore Stewart and get the Lade from the Garpel Water marked off.

Thomas White, Kameshill, to get £10 a year for going through the mines daily. Carting to be done at 6d per ton, per mile.

21st February, 1789:—Mr Grieve reported that the Furnace was now heating and would be ready for blowing in a month or six weeks.

Ironstone was now to be got from Lightshaw (Lia-shaw). Iron-ore was to be stopped unless it could be raised and laid on the surface for 5/- per ton.

Mrs Grieve to get £20 per year to entertain Friends of the Company until the Inn (Irondale) projected by Commodore Stewart be erected for public accommodation.

Lade to go at 3d per lineal yard (It now takes 3d per lineal yard to clean it).

A stable for six horses to be built.

8th April 1789—The road to Strathaven is commenced.

At meetings held at Muirkirk 29th and 30th April and 2nd and 3rd May, 1789, it was resolved to sink the High Weighs Pit to the level of the Great Mine. Also resolved to push on the Level on Tordoes Burn for both Coal and Ironstone.

Mr Edington to send five or six miners from Clyde.Resolved to write Mr Boswell that their workings at Garsewater (Gasswater—old form of pronouncing and spelling "Grass") did not warrant the erection of Furnaces there.

22nd October, 1789, held at Muirkirk.—At this time the workmen sat rent free, but this was to be altered as soon as possible. As it was found that coal in stock did not keep so well as Coke does, it was resolve to stock Coke and cover it with turfs.

John Salmond was appointed Oversman at 10/- per week, and £5 extra per year if he gave satisfaction. Thomas Darby to be stock-taker at 8/- per week, and £5 extra per year if he gave satisfaction ("That was to make them behave themselves." said Mr Baird).

Resolved that all the Carpenters shall be discharged unless those who would work for 9/- per week.

Resolved that after a trial is made of Watson's Baskets from Nether-foot, if not found to answer, it will be proper to bargain with makers about Cumnock or Affleck to furnish baskets by the piece (Mr Baird ventured the opinion that the Furnaces were filled by baskets then).

At Muirkirk, 27th August, 1790, it was resolved to sink the Kames Engine or Glenhead Pit 20 fathoms deep, and drive up the old level made by the Tar Co. to this Pit, and so save pumping water to the surface. Mr Loudon MacAdam was present, and it was resolved that all concerned would require to go hand-in-hand with all parties, before they began such an expensive operation, to prevent reflections in all time coming.

At Muirkirk, 27th September, 1790, it was agreed to build an addition to Kameshill House, according to plan. The foundation was "stabbed off." William Gardiner was to dig it out, and John Paterson was to build it. Messrs Gillies and Gordon reported that it was necessary to get a supply of good water for Kameshill House and the people at the Works.

It was agreed that the spring called Cairntable Cauldron—being the nearest, there should be laid down 2-inch earthen pipes which were to be had from Peter Moir, Potter in Drongan. That it be led in these pipes to the Reservoir near the Furnace Bank, and thereafter in 1-inch lead pipes with ¾-inch branches to the Coke Bank, John Paterson's House, and also to the Carter's House in the Barn Yard.

THE FORGE (27 September, 1790)

At this same meeting it was agreed to start a Forge either by steam or water. Two dams of two acres each were to be made, and a 42-inch Fire Engine got for working the Drawing Hammer or for Rolling.

CANAL (27 September, 1790)

It was also resolved to make a Canal 8 feet wide at the bottom, 16 or 17 feet wide at the top, and 4 feet deep, and that proper application was to be made to Mr MacAdam of Craigengullen for Liberty to bring the water through his lands of Ashyburn. Mr Salmond's work as Oversman had been good, and he was to get 7 Guineas instead of £5 as a yearly bonus, and his weekly wage was to be raised from 10/- to 12/-, with a yearly bonus of £5 as before, if he pleased.

At Muirkirk, 15th March, 1791, it was agreed to build workmen's houses near those built by the British Tar Company, at a price not exceeding eleven guineas each, being the same rate as paid for those recently built at Catchieburn (Cat-shaw-Burn) ("Eleven guineas each! There's a tip for the County Council and their housing schemes. It would now take that money to put a new hearthstone in" said Mr Baird).

A water wheel 24 feet in diameter was to be erected near the Furnace Bank, and water from the Garpel to be let to it.

THE OFFICE (1791)

On 29th March, 1791, it was agreed to build a Counting House 45 feet by 20 feet, according to plan produced (This id the Office). The building of the 12 houses mentioned above was let to Robert Willocks at £12-5-0 each, and they were to have thatched roofs. Received an account from Crossflat for damages amounting to £1-4-9.It was to be paid but Crossflat was to be informed "That the Company consider their bargain with him a very bad one!" Mr Guilland appears to have been Furnace Manager at this time, and he was to see that no drink was brought into the Casting or Bridge House on any account. He was to examine the baskets as received from the makers and see if they were right in every respect before they were paid for. Also to take care that the wheelers and fillers did not embezzle them.

22nd October, 1791.—At Glenbuck a level was being driven to a seam of coal formerly worked by Mr Whyte, and after this seam and the 6-feet seam be proved, the Company will meet and determine what further steps they are to take in regard to erecting Furnaces there before Mr Wright goes to England.

8th December, 1791.—The price of coal was fixed at: Parrot Coal 9d. per load; Chew Coal 4d. per load; and to be raised on 1st January following to 1/- and 6d. respectively.

18th January, 1792, at Glasgow.—Present Peter Murdoch, William Murdoch, and John Gillies.Mr Udney, land surveyor, having come west at the desire of the Company to meet them, and Mr Officer, to point out the proper way of sub-dividing and inclosing Tordoes Farm. It is agreed to adopt Mr Udney's plan of inclosing and planting the Tor Hill the ensuing year. The fence to be sunk and the stones to be taken from the top of the Hill to assist as far as they will go. The trees to be planted at the distance of 4 feet from each other in the following proportions:—1/3 Common Firs; 1/12 each of Ash, Birch, Oak, and Planes; a few Silver Firs; American White and Black Spruce; Holy's, Laburnams; and Mountain Ash to be added. The Bank from the Bridge westwards to be planted the ensuing season with Oaks, Larches, Beech, Mountain Ash, Laburnams, Birch, Silver and Balm of Gilead Firs, Planes, and Horse Chestnuts. The large belt of planting round the South Park to be properly filled up. The trees Mr Officer will get from Ayr. The remainder of that belt on side of the great road to be completed with same assortment as the Tore Hill. The trees for which Mr Udney will furnish and send to Muirkirk whenever the weather will permit.

On the 27th of November, 1793, the Muirkirk Iron Co. had to get the loan of £820 from the Royal Bank to enable them to carry on.

23rd June, 1796.—Three Furnaces built, but can only blow two at one time. On the 30th November, 1796, £2,000 was placed to the credit of the Company as an Operating Account, and James Gordon, Manager of the Company, was authorised to sign a Bond for this amount.

On 23rd November, 1799, Messrs Grieve and Dixon (of Dixon's Blazes probably) reported on the coal raised from Admiral Stewart's Ground.

On 9th May, 1800, William Dixon reported on all the pits going at that date. The Tar Kilns were still going.

It is reported in this connection that the Tar Kilns Dyke has been cut in two or three places, and Mr John Ferguson should be instructed to put dams into them to prevent the water flowing to the Bank Pit when the Glenhead pumping Pit was stopped. The Linkieburn Pit would at this date only last half a year longer before it came to the dyke at the West, which is a sown-throw dyke to the West of 24 fathoms. This Time Mr Dixon reported that there was Pit Room for 104 colliers.

The Report Book finished at this date, 9th May, 1800—13 years from the time the Company started, but a Letter Book starting in May, 1809, contains many interesting letters. From May, 1809, till June, 1810, they are mostly signed by Hugh Baird, who appears to have been Managing Partner at that time.

Extract from The Topographical, Statistical, and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland (1841).

————————————

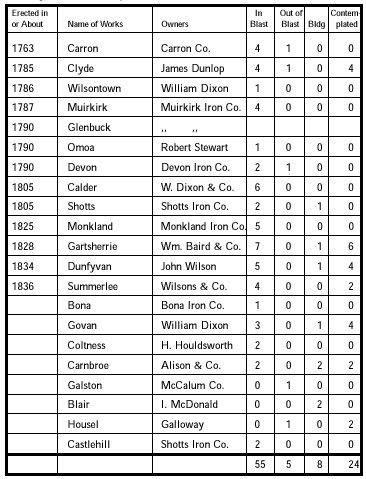

So far as our data go, there are in North Britain 55 Furnaces inn Blast; 5 Out; 8 Building; and 24 Contemplated.

With the exception of Bona, the other Furnaces in Blast are of recent date.

SCOTLAND'S FIRST IRONWORKS

Very few of the many thousands who make a living by the production of Iron know that the first Ironworks in Scotland were situated on the now lonely shores of the beautiful Loch Maree in Sutherland, yet such is the fact. There were in this district, as in other parts of the Highlands, ancient Ironworks, of which there are no historical records, and there is abundant evidence for those who use their eyes that the Rev. Donald McNicol, who in 1779 published a book entitled "Remarks on Dr Johnston's Journey to the Hebrides" was right when he affirmed that the smelting and working of Iron was well understood and constantly practiced over the Highlands and Islands from time im-memorial. He further affirms that the old inhabitants made iron "in the bloomery way," that is—by laying it under the hammer in order to make it malleable with the same heat that melted in the Furnace. At these old Ironworks the ore used appears to have been known as Bog Iron. This ore was extracted by the action of water from ferruginous rocks strata, and was accumulated at the bottom of the peat bogs, and in process of time granular masses of oxides of iron were formed, sometimes covering a considerable area, and not very far from Loch Maree there are still quantities of Bog Iron to be seen, apparently formed in this way, and analysis has confirmed the view that this was the ore used in these old "Bloomeries"—indeed, Dr MacAdam found fully 50% of metallic iron in the slag from this Loch Maree district. This waste must be accounted for by the ancient imperfect methods of smelting, the cheap labour and ore, and the apparently in-exhaustible forests whence the charcoal used was derived. It is rather suggestive that each of these ancient Ironworks, like their historical successors, utilised the water power in their neighbourhood for the purpose of working machinery, and not far away are the remains of Dams and Weirs—another proof of the mechanical skills of the old inhabitants of the North.Similar Ironworks or "Bloomeries" have been investigated in Sutherlandshire by Dr Joass of Golspie and Mr D. W. Kemp of Trinity.One of them is known to have existed on the Island of Soa, off the West coast of Skye.

But it is not because of the existence of these "Bloomeries" that it is claimed that the first Scottish Ironworks existed in Loch Maree. It appears that in 1612 Parliament ratified a License granted by the King to Archibald Prymroise for "making of 'yine' within the bounds of the Schireef-dome of Perth," but the date of the license is not known, and no more is heard of these Ironworks. The Ironworks at Glengarry, which Captain Burt refers to were said to be established by a Liverpool Company who bought the Woods in 1730.

The Iron-Smelting Works at Abernethy were commenced in 1732, by the famous York Building Company, which speculated so largely in forfeited Estates in Scotland, and whose agents and workmen in Strathspey were, according to the "Old Statistical Account," the most profuse and profligate set that were heard of in this country—"their extravagance of every kind ruined themselves and corrupted others. "They closed their Ironworks in 1734 or 1737, after making "Glengarry" and "Strathdon" PIGS, and had four furnaces for making Bar Iron.

The Loch Ettive or Bonaive Ironworks were started about 1730, and leases for these works expired as late as lately as 1884.It was in 1760 that Dr Roebuck of Sheffield and other gentlemen started the Carron Ironworks, and it was as late as 1788 ere the Clyde Ironworks were established in the neighbourhood of Glasgow, and at that time there were only 8 Pig Iron Factories in Scotland.

While the foregoing does not take you very far beyond the early years of the Muirkirk Iron Coy., it gives a good insight into their modes of procedure and history. So far as one can make out they never made much profit out of their enterprise, and at least on two occasions tried to sell their Works, and so get out of it. As is well known, John Loudon MacAdam, inventor of that system of road-making which bears his name, was a partner with Lord Dundonald at the Tar Kilns near Springhill. In 1817 the Iron Coy., anxious to get rid of their Works wrote to Loudon MacAdam after he had left Muirkirk and gone to Bristol to look after the roads in that district, to see if they could effect a sale through him. He replied advising the Company to hold on to their Muirkirk Works and Coalfields, which were very good subjects, and he was sure that in a short time things would take a turn for the better, This letter was dated 26th February, 1817, when bad trade followed after Waterloo in 1815.

The Iron Company appears to have taken his advice, and carried on, as shortly after this they borrowed money and sank the Wellwood Pit.

I will finish by reading to you the letter referred to which I am sure you will consider well worth preserving, as it shows that Mr MacAdam was a man of culture and ability. He declined a Knighthood in 1827, but accepted £10,000 from the Government for many services rendered (Sound judge again, said Mr Baird.)

TEXT OF LETTER

To James Ewing, Esq.,

Glasgow Bristol,

26th February, 1817.

My Dear Sir,

I received your letter of 21st inst. and have to lament in common with many others the pressure of the times.

The Coal Tar trade has felt the effects, as well as others of want of sale and depression of price which would be very discouraging if we did not look forward to better times.

I am at a loss to give advice you ask, as it seems you have already resolved on your measures; otherwise I should have called your attention to the fact of your having, with some other wealthy individuals, stood the worst time out—that this unfavourable time has effectively swept away a great number of Ironworks, and left the trade where it should be, with no more manufacturers than may be reasonably be desired for a supply of iron—that the great stock of iron which was in the hands of the middlemen (and which kept the market depressed un-naturally) is all gone, and therefore the supply hereafter must be got from the manufacturers. These circumstances, together with the gradual revival of trade in general seems to promise almost a certainty of the reward of those who, like yourselves, have been able to hold out through the whole time of distress. I should also have reminded you of the favourable situation you stand in, with respect to rents and lordships—the very good quality of your produce, and that you are not weighed down by the burden of a large capital in the business.

No doubt all these considerations have presented themselves to you, and I ought to apologise for suggesting them, but that you ask my opinion, and that I cannot without an appearance of disrespect withhold it. It may be objected that the new fitting your coal will be an advance of £5,000 or £6,000, but such a sum bears no proportion to the value of a manufactory of the magnitude of yours at Muirkirk, actually at work; and independent of all other considerations, the price of fitting the coal will be amply repaid by the additional strength and quality—the field being now explored in its whole length, you are free from every disadvantage and expense that can proceed from uncertainty. This expense has been defrayed by your predecessors, and you have only now to reap the advantage. I have no inducement (as my connection is of so little importance in the great scale of your concern that I am unwilling even to mention it)—I have no inducement to hold out to you that could weigh a feather in the balance; but I may be allowed to say, that I should have been most ready to prove to you how sensible I am of the very pleasant manner in which your concern have conducted themselves towards me since your purchase, and that I should have been happy if an opportunity had been given to me of showing my sense of obligation to you collectively and individually.

The only thing that deserves being named is the Kames Coal, of which about 24 acres would be won by the deep fitting, and it is certainly of the best quality and the cleanest field in the Parish. This coal is mine for sixty years after the expiry of your present lease, and as far as it could have been useful to you, I should have been ready to accommodate with a lease.

I beg you will present my respects to Mr Yule and accept my best thanks for the kind and polite manner of the communication you have made me.

I am,

My dear Sir, with much esteem,

Your Obliged and Obedient Servant,

Signed JOHN LOUDON McADAM

On the call of the Chairman, Mr Baird was accorded a hearty vote of thanks for his lecture, and in returning thanks, he said he was pleased to have had the opportunity, for he felt it not only a duty but a privilege to give this information to the Muirkirk public.

CHARLES P. BELL,

Secretary Burns Literary Association.

Mr CHARLES P. BELL

Secretary of Muirkirk Literary Association

IRONWORKS AT MUIRKIRK

Reproduced from James Taylor's Book,

"Cairntable Echoes"

________________________________

Haematite was worked at the Pennel Burn early in the 18th century. It is difficult to find an exact date. J. G. A. Baird, in "Muirkirk in Bygone Days," suggests that 1705 is too early. However, he produces an article about Muirkirk which appeared in the "Edinburgh Magazine" (1761), which says that "the Iron Forge, at which place my Lord Cathcart bestowed a great deal of fruitless labour, being obliged to desist for want of wood charcoal about the year 1730" (The Bonawe Furnace did not start till 1753).

The Haematite may have been worked at a peat or charcoal furnace (Terreoch) for a few years; then it may have been in-active, till the Argyllshire furnace, with plenty of fuel, began in 1753. Whereupon the Pennel Burn Mine was re-opened, and Terreoch resumed work as a forge, converting pig-iron into wrought iron, or perhaps as a foundry casting pots, kettles, etc., for domestic use.

We do know that the Haematite was taken by pack-pony to Ayr, about 25 miles; itn was then shipped in sailing vessels to bonawe on Loch Etive. The pig-iron was sent back to Ayr, and the ponies carried it back up to the "Old Foundry" at Terreoch, on the River Ayr, 3 miles west of Muirkirk. We can be sure that only the best ore was sent on its long journey north. In spite of this, there would be some wastage, due to inefficient furnaces and the natural impurities of the ore. I estimate that if 100 tons of Haematite went North, perhaps 60 tons of pig-iron would come back. This did not permit the ponies to trot home with light loads - they carried SALT as a s "sideline." In Ayrshire, wherever coal seams were worked near a seaport, there was a thriving export trade with Ireland. Only "large coal" was considered worth shipment, but the dross was not wasted. At Saltcoats (where the salters had their cottages), and also at Ayr, there was a thriving industry which used "free" sea-water and "dirt-cheap" dross to make salt. This was in great demand for it was the only way of preserving meat. When autumn came, and natural grass was not available, some sheep, pigs, and cattle were killed and salted in barrels to feed the family till next spring. Hence the importance of salt to an inland community. So much for history . . . . . . .

The mines are four miles E.N.E. of Sorn. They can be reached from Auchinlongford, or from Nether Whitehaugh - perhaps the easiest approach is where the horse-tramway led right up to the workings. Pits were sunk to over 200 feet, and levels were driven. The pits were active between 1872 and 1882. A deep shaft is still open (fenced to safeguard animals), and an adit can be seen in the glen. Fine specimens of kidney ore can be picked up.

The River Ayr has cut a deep channel into glacial deposits; the "1850" six-inch map names one of the meanders, immediately south of Townhead of Greenock farm as OLD FOUNDRY HOLM. It is worth a visit. A "Lade" can be traced, which fed water into the mill-pool, close beside a ruin, resembling a lime-kiln. There is a fine little arched bridge, over the "Tail-race." I quote from Baird . . . . "By water-power were the bellows worked and the hammers swung." The sandstone masonry seems to have been fused or cracked by heat (firebrick linings were probably not in use 200 years ago). The iron-workers and pony drivers lived in a little "toun" which stretched from Town to Townfoot (shown on the old six-inch map).

Terreoch foundry may be of interest to the industrial archaeologist. a "dig" in the grass-grown heaps would probably produce fragments of slag or iron, rejected castings or tools, which might tell us more about this 250-year-old Ayrshire Ironworks.