TRADITIONAL LINK WITH TAM SAMSON

(Kilmarnock Standard 7th November 1936)

|

In new countries the changes are never so great and never so outstanding, but in a country as old as Britain, the vested rights of thousands of years increased.

The difficulties which had to be overcome:

The stern laws of an old country forced things that need never be called for, where the great open spaces predominate.

A case in point is to be noticed where the railway penetrates beyond Kilmarnock in the direction of Dumfries. South east of Kilmarnock, the Railway Company had the choice of two routes. One of these was to follow the Cessnock, an engineering feat which meant many bridges and much digging. The alternative route, the one eventually followed, lay across a loch, and then it had to continue through a tunnel to Mauchline. The loch and the tunnel were almost in the land of Burns’s Mossgiel. This loch lay seven miles from Kilmarnock in a basin lying north of Mossgiel Farm. It was called the Broon Loch, but on maps the name is Anglicised into Loch Brown, and the company after consulting neighbouring proprietors – The Dutchess of Portland, Mr Claud Alexander of Ballochmyle, and a Mr George Douglas,

Finally decided to drain the loch.

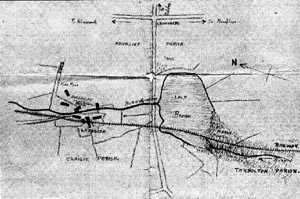

The loch lay partly in the parish of Mauchline, partly in Craigie Parish, and almost touching Tarbolton Parish. The road from Tarbolton to Galston via Largie Toll passed close to the loch, and near it, that well known place on the Carlisle Road called Crosshands.

Roughly speaking, the loch was some 50 acres in extent, but swampy land stretched right up the valley into the farm of Skeoch, and probably into the land of Mossgiel. The burn which meandered through this bog land came directly from Mossgiel. This marshy land was infested with reeds, rashes, low willows and similar scrub; it was the home of countless water fowl, frequented by poachers, and guarded by game keepers. The loch and it’s swamp was a favourite spot for Kilmarnock sportsmen, and it used to be local tradition that Tam Samson made it a rendezvous.

The overflow of this loch drained into Garrochburn, which flowed towards the clachan of Laidside, and turned the wheel of the meal mill at Dalsangan. Naturally, when the Railway Company drained the loch by a deep cutting,

They had to compensate the Miller.

His place was made into an extensive farm, and records show that he received, in addition, the sum of £400. The old charter is still in existence, and some very interesting points have never been deleted.

When the loch was drained by the deep cutting made, the water did not completely disappear. The bottom of the loch proved to be very uneven, with the result that deep puddles were left here and there. These were full of fish, and people who were old when the writer was young used to tell of the “catches” and the fish diet that was in every house at the time. The railway people filled these holes up; the ground was thus levelled to a certain extent, and today it is rich meadow land bearing grass and other crops.

It took a few years, however for sun and air to sweeten the area, but farmers eventually found the land to be very rich, and proprietors rented it at the high price of £2 per acre. Even today the land is of a black, loamy nature, though cultivation seems to be slowly changing it to red, like the “dry” land about it. The shores of the loch are still indicated every time the ground is ploughed by sand on one side and gravely stones on the other. When a deep hole is dug, the ground is found to be dark humus to a great depth. Nuts, leaves, twigs, and the like are still turned up as they were 100 or 200 years ago, but exposure makes them rot quickly into black mould. The reeds and marsh also disappeared, and rich meadow land took the place of the poacher’s paradise. There would be less rheumatics in the district probably, as many an attack could be traced to nights spent in poaching in among the reeds.

The loch was also a famous place for curling matches in winter, and the “roaring” game was played here, as it used to be on Tarbolton Loch, until recently. It is still recounted that on one occasion a wagonette of curlers from Kilmarnock drove onto the ice. The horses had to be removed and taken to the smiddy to be “sharped,” but in the meantime, the wheels of the wagonette sunk into the ice deeply and

Picks and Crowbars had to be used

To get it out. In passing, it may be of interest to say a little about Laidside, close to Dalsangan Mill, which practically vanished because the railway made it’s way right through the heart of the place.

An old name for it was Machine Close. Mr Hodge, the present occupier of Dalsangan, a gentleman well versed in local lore, thinks this name may be due to the large smiddy that stood there, in which probably some of the very earliest farm machinery was made. The clachan had round about a dozen families, and from the plan of the place it would appear that overcrowding is by no means a new evil. The Lambies, Stirlings, Kennedys, Wallaces, Robbs, Manns, Smiths, etc cannot now be traced; they simply disappeared when the railway brought down their homes. There was in addition to the meal mill, a flax mill there. The smiddy was removed to Crosshands, and it is interesting to record that Mr Elliot, the smith there until quite recently, was a descendant of the smiths who worked at Laidside.

Laidside now consists of One House

Laidside must have been a place of great antiquity. Some years ago when workmen were laying a waterpipe along the present roadway, they discovered an old pit shaft, scantily bridged over. The walls of this pit were stone built and in perfect condition. The depth when the pit was laid open was 12 fathoms, and the refuse of the pit still makes a slope in the roadway. It would appear that the monks of Fail, a monastery near Tarbolton and a ruin for centuries, were reputed to have mined coal more or less on the outskirts of their domain. The chances are that this was one of these old pits, and Laidside must have been one of the earliest coal mining villages in the world. The first train which passed over the drained loch was seen in 1848, and the schoolmaster at Crosshands took his pupils down to Laidside so that

The Sight might Live in their Memory.

The loch was probably drained a few years before that. A Roadway at that time came from Carnell (or Cairnhill as it was called), circled round through Laidside, and then proceeded direct to the main road from Kilmarnock to Mauchline. The road now passes by the present Laidside, a smallholding and the only house left of the clachan, alongside the cutting in which the burn runs, to join the Galston Road that passes through Crosshands. Before the war, a large plantation of tall trees hid Crosshands from view, but this has now disappeared, and the acres lie down in rough grass.

To those who know Burns country well, it will prove interesting to learn that Tam Samson used to shoot over the marsh land around the Broon Loch, and as the marsh stretched almost if not quite up to Mossgiel, it is not beyond possibility that these old friends met at sometime, either at the farm or by the loch. The tradition was handed down by James Mair, farmer in Lochhill, at the beginning of the present century. This farm overlooks the area of the loch. James himself used to work as a brakesman on the railway, and it was he who recalled the deep puddles and the fish. Burns would have to pass near the loch when he went to market at Killie, and the broad stretch of water must have been an interesting feature of the countryside in his time. H.H.A

Loch Brown Page

Mauchline Home Page