| The

Mills of the River Ayr John R. Hume, B.Sc. |

Photos of Mills around the Sorn Area

From

"Ayrshire Collections" Vol 8, 1967-1969, published by George Outram & Co, Kilmarnock, for Ayrshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. Reproduced by kind permission of the family of joint editor of "Ayrshire Collections", the late Dr John Strawhorn. Dr Trevor Matthews, the current Hon Secretary of the Ayrshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, has also given written permission to use the original article. |

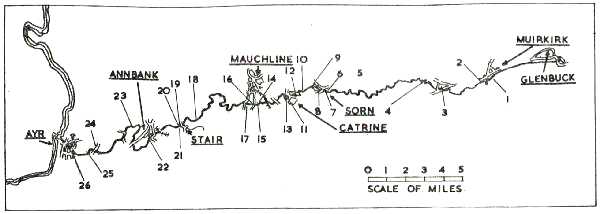

Mills described in the text About 1850 the River Ayr provided power for as many as fifteen industrial establishments, and by that time there were at least ten other disused millsteads. Since then, decline has been slow but continuous. In 1967 the only water-power sites are the Catrine cotton mill and bleachworks of James Finlay and Company, and the Dalmore factory of the Tam O' Shanter and Water of Ayr Home Works Limited, both of which are supplied with electricity by private turbo-generators. Other sites survive, but much altered. In this article the history of the mills of the river will be discussed, and their present condition recorded. The River Ayr rises in the hills to the north of Glenbuck Loch, a picturesque sheet of water situated near Muirkirk. The loch was created in 1802 by James Finlay and Company to provide a reservoir for their Catrine mills, and another artificial reservoir, 21 acres in extent, was constructed a short distance downstream in 1808 to give more storage capacity. (1) The second reservoir is now disused, but Glenbuck Loch still stores water for the Catrine generating system. The first works to use water power below the reservoirs was Muirkirk Ironworks, founded in 1787 by a group of Scottish wrought iron users. (2) The site of the works was determined by the availability of a suitable fall of water, and the alternatives of an earth dam 150 yards wide and 30 feet high providing storage and a short lade to the wheel, and a long water cut on the south bank, were both considered. (3) The latter course was adopted, and although a steam blowing-engine was erected, when a second furnace was contemplated in 1788, the building of a water-powered blowing-engine was again discussed. (4) Eventually a water forge was built to process the crude wrought iron from the puddling furnaces. (5) An earlier wheel, constructed to drain the coal near the furnace bank, was fed from the Garpel Water, a tributary of the Ayr. (6) A third wheel to drain 'the first Air pit on Catchy Burn level' was authorised on 22 December 1789, and tenders sought. The pit was to be 25 fathoms deep, the 'working barrell' of the pump nine inches and the 'common pipes' ten inches in diameter. (7) The long lade from Ashaw Burn to the furnace bank was wide enough and deep enough for it to be used as a canal connecting various ironstone and coal pits with the furnaces, and it continued to be used at least until the late nineteenth century. Though drained, its course and the basin at the furnace bank can still be traced. Downstream from the ironworks, the first corn mill on the river was Aird's Mill, tenanted by William Aird in 1851. The site has now been cleared, though a small square shed may incorporate part of the mill buildings. Parts of the lade can still be seen. The mill was an L-shaped structure on the north bank of the river. Mr. James S. Wilson, writer of an unsigned series of articles on the corn mills of the River Ayr which appeared in the Ayrshire Post in 1944-5, confused Aird's Mill with a waulk mill which was powered by the Ashaw Burn, a tributary of the Ayr. Two and a half miles to the west of Aird's Mill, near Nether Wellwood farm, stood Muirmill, on the north side of the river. The buildings here have disappeared, but a long lade can still be traced in places. The mill had one pair of stones driven by a breast paddle wheel. Before the collapse of the Ayr Bank, the mill and the farm of Dalfram were let by the Earl of Loudoun, to John Lapraik. Lapraik retained the mill after his financial crash until 1796. He was a friend of Robert Burns. (8) On the south bank of the river, and a further one and a half miles downstream, a forge was built near Townhead of Greenock by Lord Catheart about 1732. Although shown on Armstrong's map (1775), it was disused by the end of the eighteenth century. The lade system can still be distinguished: it branches into two, which would imply two wheels, the normal number in a forge, where one was required for the bellows and the other for operating a tilt' or helve hammer for forging. The statement that local ore was shipped to Bonawe for smelting may have been true after 1753, but before that time a bloomery, or primitive blast furnace, might have been used. (9) This site, known as Terreoch, would repay careful excavation. The next mill to be encountered is Holehouse Mill, now ruinous, with walls two to five feet high. Constructed of river boulders set in mortar, with their outer faces roughly dressed, the walls are all two feet thick, with the exception of the wall supporting the wheel bearing, which is two feet four inches thick. A detached square building may have been a kiln for drying grain. Though the lade has been filled in, its route can roughly be seen. Whether this mill was used for the commercial grinding of grain in recent times is doubtful. Certainly the tenants in 1851 and 1868 were farmers, (10), and the buildings were occupied as a farm in living memory. (11) A low circular platform about thirty feet in diameter, of rubble and earth, on the west side of the mill building may have been a threshing floor or the site of a horse-gin. Sorn (or Dalgain, as it was formerly named) has had at least four water-power sites. On the south bank, traces of a lade and a cottage named 'Wheelhouse' are all that remain of a millstead, which has disappeared. On the same bank a quarter of a mile downstream, a lint mill is reputed to have existed. No trace remains, but the two mills, which were built on the north bank, have left more substantial buildings as memorials, though both have been out of use for more than fifty years. New mill, which took water from a curved weir, was a worsted mill. This mill is not mentioned in the New Statistical Account, but is shown on the first edition of the six inch Ordnance Survey map (surveyed 1856). In 1855 one Thomas Hendry is mentioned as a 'worset' spinner in Sorn, and the mill remained in the hands of the Hendry family until 1901, when the estates of Thomas Hendry and Son, Worsted Spinners, and of William Hendry, then sole partner, were sequestrated. (12) Thereafter the machinery was removed, and for a time the mill building was used as a woodworking workshop, where fiddles for good seed sowing were made. Now the building, which was shortened about 1930, is used partly as a slaters' store and partly as an old men's recreation room. (13) (NB: Ample remains / ruins of Lintmill can be seen on the banks of the River Ayr opposite Morton's Garage.. . . ayrshirehistory.com) Dalgain mill, about half a mile west of New mill, was the Barony mill of Sorn. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the mill changed hands several times; in 1851 the miller was Hugh Wilson, in 1868 David and Robert McNay occupied the mill, while in 1890 William Gray was miller. Closed about 1913, it had a breast paddle wheel, with three pairs of stones for oatmeal and provender. (14) The building, in good repair, is a two storey and attic rubble-built structure with a slate roof. After a short period as a creamery, the mill building lay empty until converted into halls for Sorn Parish Church. From this conversion date the large skylights. Nearly a mile downstream, there was a waulk mill on the north bank of the river, which was disused in 1856. (15) This small textile finishing mill has now disappeared, but only a few hundred yards away are the Catrine bleachworks, part of the largest water-power complex in Ayrshire. Before David Dale and Claud Alexander planned their cotton mill in 1785, a corn mill with one pair of stones had been almost the only building on the flood plain of the Ayr, which was to become the site of the new village. The end building in the present Cornmill Street may well incorporate part of this structure. (16) A corn mill, constructed in 1790, (17) is shown on this site on the plan of Catrine, dated 7 January 1797, which was included in the Old Statistical Account. (18) In the retaining wall at the end of Cornmill Street is a blocked-up archway, which was probably the tailrace of the grain mill. Much more important than this little mill, however, were the great cotton mills and bleachworks. The water supply for the first mill, the so-called Twist Mill, which formerly stood in the centre of Mill Square, was drawn from the river about half a mile upstream. A curved weir was constructed of a silt-clearing design, with self-acting sluices, and the lade passed through a tunnel ten feet in diameter to a point opposite the mill, whence a series of arches led the water on to the wheel, which was on the east side of the building. This large mill, five storeys high, stood until the early 1960s, when it was destroyed by fire just as demolition was about to commence. In 1790 a second mill was built to house seventy six spinning jennies. This so-called Jeanie Factory', which stood on the site of the present mill, was also water powered. (19) In 1801 James Finlay and Company acquired the mills, and at some time in the early nineteenth century the first wheel was replaced by one of mixed wood and iron construction. In 1824 a bleaching works was put up, and has since been extended several times. Archibald Buchanan, the manager, who had trained under Arkwright at Cromford, was responsible for an extensive reorganisation of the water power system in the late 1820s. Reservoirs were constructed between the dam and the mill, and three large water wheels constructed. (20) These were designed by William Fairbairn, and incorporated his latest improvements in water wheel construction, including the use of light wrought-iron spokes, with power taken from the rim of the wheel. Originally four wheels of a hundred horsepower each were planned, but only two were built, by Fairbairn's own firm, Fairbairn and Lillie of Manchester, in 1827. With a diameter of fifty feet, ten feet six inches wide, and having a hundred and twenty buckets, each of these wheels actually developed a hundred and twenty horsepower. They were the largest and most powerful wheels in Scotland when built, and through a larger wheel, seventy feet in diameter, was installed at Greenock in the 1840s, the installation remained without equal for power until its demolition in 1947. The drive to the mills was carried under Mill Street in a tunnel, while the tailrace, as before, flowed down the street and continued in tunnel for a further quarter of a mile to the mouth of the Burn 0' Need. This was a device of Fairbairn's to increase the head of water available. (21) The outlet of the tailrace, now partially blocked by silt, can still be seen, as can the arches which led to the wheelhouse. These two great wheels were not, however, the only ones associated with the works in the bleachworks. A fifty horsepower wheel drove the wash wheels, mangles, calendars, beetling machines and hydraulic presses, while in the foundry. A fifteen horsepower wheel drove the cupola blowing engine and machine tools. (22) Taken as a whole, the two hundred and ninety five horsepower developed by the four wheels made Catrine one of the biggest water-power concentrations in Britain. The new mills, opened in 1950, are powered by electricity generated by water from the Ayr, and the weir, part of the lade, and the reservoirs still supply the modern turbo-generators, installed in 1952. Thus a link with the earliest days of cotton manufacture in Ayrshire is maintained. About two and a half miles downstream from Catrine, on the north bank of the river, stand the few surviving houses of the village of Haugh. In 1837 there was a woollen mill, and a corn and saw mill here, drawing water from a dam about a quarter of a mile upstream. The lade was tunnelled through the soft red sandstone of the river gorge, and the tunnel mouths can be seen, as can two stone arched footbridges over the lade, and an overflow sluice. All traces of the woollen mill, which in 1837 employed thirty persons Spinning yarn for a Kilmarnock carpet factory, (23) have disappeared. The corn and saw mill still stands, though now empty of machinery. A two storey and attic building with a slate roof, the site of the water-wheel, can still be seen. There was apparently a third mill at one time, further downstream on the same lade, probably on the site of the present spectacle-frame factory, formerly the Ballochmyle Creamery. (24) On the south bank of the river, about half a mile below Haugh, is Barskimming mill. The lade, which can still be seen, was widened and deepened about 1834, when the present road to the mill was constructed. The mill at that time had two wheels, which drove six pairs of stones, two for shelling oats, one for finishing oatmeal, and the other three for flour and provender. Of four storeys, with a sunken flat, the building had a large double kiln with a fan to force the draught. In the late eighteenth century the mill was occupied by James Andrews, an acquaintance of Burns, and it was lighted by coal gas by his grandson, also James Andrews, who was a millwright of considerable ability. Andrews' successor, William Alexander, modernised the mill and carried it on until its destruction by fire about 1893. He then replaced it by the present mill, a four storey brick building with stone quoins, which was operated by Charles D. Ross until 1959. In the early 1950s, it employed thirty three men producing cattle food, including the processing of 3000 tons of oats annually. (25) After closure the machinery was removed, and then the mill remained empty until 1962 when D. and W. Miller and Company (Pressings) Limited took it over as a light engineering factory. It is now known as Barskimming Works. (26) Clune Mill has long since disappeared. Though shown on Armstrong's map (1775), it does not appear on the 1856 Ordnance Survey, and no trace can be found on the site. It had only one pair of stones, and the meal was sifted by hand. A short distance down the river is the dam for Milton Mill. The lade at one time served a lint mill, as well as the corn mill, and later a grass-seed cleaning mill belonging to Messrs. John J. Inglis and Sons. For a short time there was a curling stone factory and a hone mill belonging to Messrs. Donald V. McPherson and Company. The corn mill was two storeys in height, with a 'broken loft'. This had a platform on which were two pairs of stones-one for shelling oats and the other for finishing oatmeal-driven by a crown gear-wheel. On the second floor a third pair of stones for flour and provender was driven through overhead cast-iron bevel gearing. The wheel was of the breast paddle type, fourteen feet in diameter and four feet wide, developing about fourteen horsepower. The millstones were large, two pairs being of French burr, four feet ten inches in diameter, and the third of Kaimshill stone, five feet in diameter. The runner (upper stone) of the latter weighed thirty hundredweight. A bouton machine was provided for grading and dressing the flour, and there was a barley mill for making pearl barley. There was a large corn loft with a medium sized kiln. After its closure in 1902, it was purchased by the Water of Ayr and Tam 0' Shanter Hone Works Limited, and is now used as a workshop. (27) Power is supplied by an Eseher Wyss turbine, itself a replacement of an earlier machine, which generates electricity to power stone saws and grinding machines and to light the works. Nearly opposite Milton Mill, and connected to it by a suspension footbridge, is Dalmore Mill. A T-shaped two storey stone building, harled and now asbestos-roofed, it retains the decaying skeleton of a wooden low breast paddle wheel with a cast iron axle. It may well be the mill referred to in the New Statistical Account as having been erected for pulverising graphite, which was mined locally. After that scheme was abandoned, the mill was extended and used for carding wool. By 1841, however, it was used only for the dressing of whetstone. (28) On the building is a carved stone depicting a sheaf of corn, and bearing the inscription W. Heron, 1821. This would seem to indicate that the mill was built as a corn mill; the Herons were the proprietors of the lands of Dalmore. Although its origins are obscure, Dalmore Mill has been processing whet-stones for well over a hundred years. The stone occurs locally, and has been formed by the baking of a bed of 'calmy blaes' by sills of dolerite, which have intruded above and below. Originally quarried, the stone is now mined, and cut to size, together with imported stone, in Milton and Dalmore Mills. More than sixty workers are employed, and most of the output is exported. (29) Privick Mill is about two and a half miles downstream from Dalmore. A low weir supplied water through a lade about a quarter of a mile long and ten to twelve feet wide. Much of the weir and lade were swept away in the floods of August 1966. There were two mills here, each with a breast paddle wheel fifteen feet in diameter and four feet wide. The older of the two mills was originally two storeys high, with a broken loft. It had two pairs of stones and a barley mill with its own water wheel. In about 1858 it was taken over by James Craig who extended it to three storeys, added three pairs of stones and built extra storage buildings. At about the same time an entirely new flour mill was constructed, four storeys high, with two pairs of French burr stones, a smutt machine, a bouton machine with a mixer and cooler, and a kiln at the north end of the mill. The flour mill had only a short life, as it was quickly superseded by the city roller mills. (30) The mill was again rebuilt in 1897, but was completely disused by 1938. In 1939-40 the surviving water wheel was used to drive a generator supplying electricity to the mill, millhouse and nearby nursery. Though all the machinery was removed in 1945, the buildings are in reasonable condition, and are used as a store. In the garden of the mill house is a decaying French burr stone, while two pairs of stones went to a garden in Mauchline belonging to Lady Glenarthur. (31) About three miles down the river from Privick Mill is Auchincruive, now the Glasgow and West of Scotland Agricultural College. Here the floods of August 1966 tore away part of the riverside walk, where a whin dyke crosses the river forming a natural weir, to uncover a portion of wall and an arched bridge over a lade cut through the dyke. Further excavation revealed that the wall, about two feet thick and built of roughly dressed blocks of stone, was parallel to the rock cutting. The cutting was about five feet deep by four feet wide, and the arch left about two feet of headroom for the watercourse. The head of water available, three or four feet, would mean that an undershot or low-breast wheel must have been used. No written record of this mill is known, and its discovery fills a gap in the pattern of corn mill distribution on the river. The choice of site was a good one. The natural waterfall would require only minor repairs to make it an effective weir, but the mill must have been very susceptible to flooding, and the power developed must have been small. By analogy with comparable mills, there was probably one pair of stones, and the machinery would have been all of wood. The Oswald of Auchincruive Papers in the Scottish Record Office (32) do not shed any light on the date when this mill was in operation, and as no dateable material was discovered on the site, any accurate dating must depend on the discovery of fresh evidence. One theory is that the mill was disused when Richard Oswald purchased the Auchincruive estate in 1764, and that it was demolished when the riverside walk was constructed. Certainly by 1856 it had disappeared. (33) The mills associated with the town of Ayr are very ancient. The Over and Nether Mills belonged to the Dominicans in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. But when the Reformation came, the mills were returned to the burgh, which had owned them originally. (34) Dalmilling, or Milton Mill, was held in the 13th century by Yorkshire nuns and canons of the Gilbertine order, who had been invited to Ayr by Walter, the second High Steward. In 1238, the land and mill were transferred to the monks of Paisley, who held them until the Reformation, when the mill was granted to Lord Claud Hamilton. Thereafter the mill passed through several hands, and was bought by Mr. Campbell of Craigie in 1790. The mill was still in existence in the first half of the nineteenth century, but had disappeared by 1856. (35) The Newton or malt mill, situated at the foot of Main Street, Newton, was in fact powered by a tributary of the Ayr, and was not, therefore, strictly one of the mills of the River Ayr. (36) The Over and Nether Mills both survived into the twentieth century, and indeed the Overmills were not demolished until the spring of 1963, although the Nether Mill disappeared in the early 1950s. The Nether Mill was a three storey, and attic whitewashed stone building supplied with water from a curved weir, which in earlier times incorporated salmon 'cruives' or traps. The weir is the upper limit of the tidal stretch of the river, and is intact. The stone breastwork on the south bank of the river, which protected the wheelhouse and parts of the walls of outhouses, can still be seen. The site of the mill itself is now a car park. (37) The Overmills are the best documented of all the corn mills on the river. Four storeys high, with an attic, the mills were extended at least twice in the nineteenth century. As they existed in the 194Os, the mills had a curved weir of silt-clearing design. This has now been breached, and the construction can now be observed. A rubble core is covered with a masonry facing, to resist the eroding action of the water. Water was taken from the south end of the weir, and passed through an iron grille and along a short lade to power a breast paddle wheel twenty feet in diameter and five feet broad, which developed about thirty horsepower. There were five pairs of stones, three driven from a crown wheel, one from a countershaft through bevel gears and the fifth by belting. The last named were for oatmeal and oat shelling respectively, while of the other three, two were originally used for flour, and the third for provender. Latterly all three were used for provender. Two sieves were provided for removing seeds from the oats, and a third for grading the oatmeal. The sack hoist, of the normal screw friction type, was built by J. and A. Taylor of Ayr. A large kiln with forced draught could dry about a hundred bushels of grain at a time. Considerable trouble was experienced with 'back watering', which flooded the wheel, rendering it useless. At times the mills could be stopped for a week for this reason. (38) In an earlier reconstruction, a new water wheel, fourteen feet in diameter and three feet wide, to drive two pairs of stones, and such auxiliary machinery as fanners, a bouton machine, a rack-operated sluice and a sack hoist were designed by Solomon Gillies of Newton on Ayr, at an estimated cost of £256 7s. 3d. excluding structural alterations. The plan was submitted to John McKell of PartickMills, near Glasgow, who recommended enlargement of the wheel and stones, and some alterations to constructional details. Taking into account these modifications the total cost of the reconstruction was estimated as £531 13s. 4d. Economy was effected by the re-use of old materials, but extensive use made was of imported timber, Memel fir,in the construction of the wheel and mill framing. Cast iron was used for the stone pinions, spur wheel, and the teeth of the pit wheel, while the stone spindles and "fit boxes" (bottom bearings of the spindles) were of wrought iron. The building was slated with best Easdale slates set in mortar, over Memel fir roof timbers. The estimates were prepared in 1806, and it seems reasonable to assume that the work was completed within a year. (39) The dating is significant. Grain prices were rising and so the profitability of milling increased during the Napoleonic Wars. Many Scottish mills were extended and re-equipped at this time. The Overmills were the last operating grain mills on the river, but were demolished in the spring of 1963. The mills of the River Ayr then, present in microcosm the history of water power in Scotland. The first mills were the corn mills-some monastic in origin, growing in number as arable farming grew until the eighteenth century. The abolition of multures and road improvement removed the need for a large number of small mills, and grain milling became concentrated on such sites as Barskimming and Privick Mills. At the same time the preparation of flax for spinning, and the fulling of woollen cloth, gave rise to lint mills and waulk mills which had their representatives on the Ayr at Sorn and Catrine. The coming of large-scale industry in the 1780s resulted in the creation of Muirkirk Ironworks and Catrine Cotton Mills, both Ayrshire pioneers, while the worsted and woollen mills at Sorn and Haugh were typical of the many small textile establishments which grew up in south west Scotland in the early nineteenth century. Further transport improvements and the introduction of steam and then electric power liberated industry from its dependence on water power. The reluctance of concerns such as James Finlay and Company and the Water of Ayr and Tam O'Shanter Hone Works to move from their traditional sites reflects the existence of other local advantages rather than the virtues of the Ayr as a source of power. This account of the mills of the Ayr is unfortunately incomplete. It suffers from the opinion of eighteenth and nineteenth century writers that water mills were too common to be interesting. Legal papers give indications that mills existed, and who occupied them at different times, but are silent as to site and equipment. In this article, the author has tried to make sense of a large number of scattered references. He has drawn heavily on the work of the late Mr. James P. Wilson, author of the Ayrshire Post articles, and himself a miller on the Ayr. He is most grateful to Mr. J. W. Forsyth of the Carnegie Library, Ayr, for drawing his attention to Mr. Wilson's articles. Unfortunately Mr. Wilson's notes have been lost, so his sources remain a mystery. The

author is also very grateful to Mr. J. Gibson, Woodlea, Sorn. D. &

W. Miller & Co. (Pressings) Ltd. Mr. J. C. Gilchrist, Privick

Mill Nursery. Mr. Alexander Wilson, Millmannoeh Mill, Drongan. Dr.

J. Swarbriek, Glasgow, and West of Scotland Agricultural College,

Auchincruive. Mr. Wm. M. Ramsay, "Adinfer", 18 Quail Road, Ayr. Dr.

J. Strawhorn, 2 East Park Avenue, Netherplace, Mauchline. The Water

of Ayr and Tam O'Shanter Hone Works Ltd. His colleagues Dr. 3. Butt

and Dr. 3. T. Ward. The staff of the Mitchell Library and the Andersonian

Library, Glasgow, the National Library of Scotland, and the Scottish

Record Office, Edinburgh, for all the help they have given in the

preparation of this article.

References: 1) Muirkirk Iron Company MS Lease Book 1787-1815, pp. 188-196 (part of the Baird MSS. on loan to the University of Strathclyde); J. Paterson. History of Ayr and Wiglon. (Edinburgh, 1863) p. 604. Glenbuck Loch G.R. NS 755285. other reservoir NS 745285. 2) J. R. Hume and J. Butt, Muirkirk 1786-1802, The Scottish Historical Review, XLV 1966, pp. l60-l83. 3) Muirkirk Iron Company MS Sederunt Book, 1787-1800. pp.14-16 (part of the Baird MSS, on loan to the University of Strathclyde). 4) Ibid., p.30, copy letter Thomas Edington to John Grieve, Cramond, 9th April, 1788. 5) Muirkirk Iron Company MS Letter Book 1809-1812, copy letter Duncan Stewart to Mr Baird, 3rd July, 1809, mentioning that a tooth on the pinion wheel at the water forge drawing hammer had broken. 6) Muirkirk Iron Company MS Seredunt Book 1787-1800, p.51, minute of meeting on 8th April 1789 mentions a lead (lade) three feet wide at the bottom, nine feet wide at the top and three feet deep, which was to cost 1s 6d. per running fall of l8.5 feet, and p.55 "the water wheel is meant to be driven by the Garpell water". 7) Ibid., p.65. 8) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr, The Ayrshire Post, 1st September 1944. 9) J. G. A. Baird, Muirkirk in Bygone Days, (2nd ed.. Muirkirk, 1940), pp.23-4. Shown as a forge on Armstrong's Map of Ayrshire 1775. 10) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (ii), The Ayrshire Post, 22nd September 1944. 11) Communication from J. Gibton, woodlea, Sorn. 12) Disposition by James Weir and Hugh Sharp, Trustees of John Lapraik, to Thomas Hendry dated 12th and 18th April 1855; Act and warrant in favour of William Dunlop as Trustee on the sequestrated Estates of Thomas Hendry and Son, 2nd August 1901. These deeds were kindly loaned by J Gibson, Woodlea, Sorn. 13) Communication from J Gibson, Woodlea, Sorn. 14) Anon.. Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (II), The Ayrshire Post, 22nd September 1944. 15) First edition of the Ordnance Survey map of Ayrshire, six inches to the mile, surveyed 1856. The mill was in use in 1797, see Sir John Sinclair (ed) The Statistical Account of Scotland (1798), volume 20, p.146. 16) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (II), The Ayrshire Post, 22nd September 1944. 17) Anon., James Fintay and Company, 1750.1950, (Glasgow, 1951), p.55. 18) Sir John Sinclair (ed.), Statistical Account of Scotland, (1798), volume 20, facing p.185. 19) Anon., James Finlay and Company, 1750-1950, (Glasgow, 1951), p.55. 20) ibid., p.62; also Helen J. Steven, Sorn Parish: its History and Associations. (Kilmarnock, 1900), p.62. Apparently the wood from the second wheel was used in the Mauchline snuffbox factory. Miss Steven quotes, a poem written about this wheel by a mill employee. 21) William Fairbairn, Treatise on Mills and Millwork (2nd ed., 1864) pp.129-133+2 plates. 22) Anon., James Finlay and Company, 1750-1950 (Glasgow, 1951), p.65. 23) New Statistical Account, (1842), v, Ayrshire, p.164, (essay dated July 1837). 24) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (IIII), The Ayrshire Post, 29th September,1944. The saw mill may have been associated with the snuffbox factory mentioned in the New Statistical Account, which employed 60 persons in 1837. 25) Ibid., also 3. Strawhorn and W. Boyd (ed.), Ayrshire, (Third Statistical Account of Scotland, 1951), p.700. 26) Communication from D. & W. Miller & Co. (Pressings) Ltd. 27) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (Iv), The Ayrshire Post, 10th Novemher 1944. 28) New Statistical Account, (1842), v. Ayrshire, p.638, (essay dated December. 1841). 29) J. Strawhorn and w. Boyd (ed.), Ayrshire, (Third Statistical Account of Scotland, 1951), p.714. 30) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (VI), The Ayrshire Post, 24th November 1944. 31) Communication from J.C Gilchrist, Privick Mill Nursery, Auchincruive. 32) Scottish Record Office: GD 213 Oswald of Auchincruive Muniments. 33) First edition of the Ordnance Survey map of Ayrshire, six inches to the mile, surveyed 1836. 34) A. I. Dunlop (ed.). The Royal Burgh of Ayr, Edinburgh, 1953). pp 98-9. 35) Anon.. Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (VIII), The Ayrshire Post, 19th January 1945. 36) A. I. Dunlop (ed.), The Royal Burgh of Ayr, (Edinburgh, 1953) p. 82f. 37) Communication from Wm. M. Ramaay, "Adinfer", 18 Quail Road, Ayr. 38) Anon., Corn Mills of Ayrshire: The River Ayr (VIII), The Ayrshire Post. 19th January 1945. 39) Scottish Record Office. RH 2560 Plan of Mill at Ayr. |